Really, the book is about yoga for chronic illness and chronic pain.

If you live with chronic pain, you’ve probably had at least one well-meaning friend tell you, “oh, you definitely need to do yoga!” (Or so I am told by my friends who live with chronic illness.) I was surprised to see Cory Martin, a person who lives with chronic pain due to MS and lupus, not just make this suggestion, but also write an entire book about it. Now to be fair, Ms. Martin was doing yoga (and teaching yoga) before she received either diagnosis, so she may have been more receptive to the idea than most; more important, she has the lived experience to back the suggestion to do yoga AND the chops to suggest appropriate practices and how to work with your body.

Disclosure: I was lucky to get the opportunity to access an advance readers copy of Ms. Martin’s forthcoming book, The Yoga Prescription. This listed publication date for this book is January 11, 2022. Access to the ARC did not require me to do anything, though of course the publisher did ask for any private feedback I might want to share. I think this book has merit and may be actually helpful for people living with chronic pain, as it was written by an author who is walking in those shoes; this is a book most yoga teachers are 100% unqualified to write—I could try to write a book like this, but I would not be credible since I do not live with chronic pain. There is a lot of autobiography that I found educational or enlightening, but the target audience will likely recognize as similar to their own experiences. Because of this, I decided to write a review on my blog.

Prior to reading this book I was totally unfamiliar with Ms. Martin as an author (though I later realized I’ve seen/read some of her prior work, unaware it was hers). The introduction introduces you to Ms. Martin and the fact that she lives with multiple sclerosis and lupus. This is continued in chapter 1, “the diagnosis,” which is also largely autobiographical. Chapter 2, “understanding the treatment plan,” introduces basic concepts in yoga. The remainder of the chapters have a yoga-related or yoga-informed title that is also a mental attitude or practice and a physical practice associated with them (“be here now,” “just say no,” etc.) Each of these chapters also features one yoga pose or yoga-related practice suggestion.

The Yucky Parts.

On the theory that it’s best to end on a positive note, I’m going to start with what I disliked about The Yoga Prescription.

The title. This book is not a prescription; yoga is not medication. While some yoga may be “prescribed” by a qualified physical therapist, medical practitioner, or trained yoga therapist, this isn’t that kind of yoga. The book fails to “prescribe” anything specific and in fact one of the main themes of the book is the exact opposite: yoga practice has to be personalized to your body on the specific day you are practicing.

The subtitle. “A Chronic Illness Survival Guide.” Only semi-accurate. Based on the title and subtitle, I expected to see more of a step-by-step process. Like “Chapter 1: How to yoga after your diagnosis” or something. Instead, the introduction and first chapter are autobiographical, as is about one-half to one third of each subsequent chapter. My read is that the chapters follow Ms. Martin’s experience somewhat chronologically, while the practice suggestions build on each other starting from chapter one. There’s not quite enough material to separate the biography from the yoga suggestions, and I do quite like the mix of experience plus practice suggestions. Yet I still find the subtitle as misleading as the title.

The cover. I really hope this cover changes before publication (and it might—the cover mock-up on the ARC is often not the final cover). Since the book has not been published yet I do not have a photo to show you. The cover is a blue background with a horizontal rectangular box that is yellow, with three pill capsule graphics underneath (the kind where there are two colors, one for each half of the capsule). The word “yoga” appears in the yellow box, and each of the three pills has part of the word “prescription” on it (pre-, scrip, -tion). Not only does this feel pretty stale to me—I’ve probably seen a dozen books with pills on the cover in the past—it’s an active turn-off. If I saw the cover at a bookstore, I’d pass right by without picking it up.

The explanations of Sanskrit terms. One of my pet peeves is the gross oversimplification of Sanskrit words in general (and yoga terms specifically) in the western presentation of yoga. This isn’t a pitfall unique to Ms. Martin—to be fair—but as she has more than 500 hours of yoga teacher training, it’s a bummer to see her continue the trend of dumbing-down yoga. For example, in Chapter two, the introduction to yoga, Ms. Martin writes: “Put simply, yoga means to yoke or bring together.” Except that’s not true.

The meaning of “yoga” is more complicated than saying the Spanish word “rojo” means “red” in English. Yes, the word “yoga” comes from the same root word that led to our English word “yoke,” but that’s not an accurate translation of the word yoga. As I learned from Anya Foxen (PhD) yoga is a super basic, super generic word. It means fixing a bow; employment, use, application; equipping or arraying an army; a remedy or cure; and a means, device, way, manner, or method…among many other meanings. The concept of yoga as meditation doesn’t show up until half-way through a rather lengthy list of definitions, though many American yoga teachers tell their students all yoga practice is driving toward meditation. As Ms. Foxen explained, yoking and chariots were the high-tech of the time, and the word yoga as yoking a chariot was the appropriate high-tech metaphor of the time—much like in the Renaissance we see finely-tuned clocks as the high-tech leading to the analogy “runs like clockwork,” or how us moderns talk about the brain as a computer. This concept of yoga as yoke is more like the word “rig” (another definition of yoga) as used in the nautical sense, and also in the sense of a trick, stratagem, or fraud (like rigging an election or rigging the game).

It would have been really interesting to see Ms. Martin tie the complicated multi-faceted word “yoga” to the equally complex challenges of living with a chronic illness that is not visible to others. (M.S. and lupus rarely have visible symptoms; you don’t “look disabled” or “look sick” to others.) I understand that Ms. Martin is aiming for a beginner audience, but this gives her the perfect opportunity to educate instead of to repeat the tired half-truths of yoga teachers past. Even if she did not want to include this much information in the introduction to yoga chapter, she could easily have thrown it into an appendix or other supplemental material at the end of the book. It’s a pretty short book, there was plenty of room left. (I’m not even going to start on the “translation” of “namaste,” but suffice to say it repeats an American invention and is not a translation.) This is just one example of the watering-down of the terms used to talk about yoga that Ms. Martin repeats.

The Yummy Parts.

Let’s talk about things I loved about the book.

This isn’t a book about “yoga poses.” (Yes, there are yoga poses included. But if you’re looking for a book about yoga poses, you might try Ms. Martin’s earlier book, Yoga for Beginners.) While the chapter introducing yoga does make it sound like Patanjali is the be-all end-all of what yoga is (he’s not, but most western yoga can be traced by to Krishnamacharya and/or western European esoteric practitioners, all of whom emphasized Patjanjali and more or less ignored other historic texts), it clearly sets out that there are eight parts of yoga. While I take issue with her Sanskrit “translations” throughout the book, I love the way she explains how each of the yamas and niyamas—these are the ethical precepts of yoga, sort of like the “thou shalts” and the “thou shalt nots”—relates to her experience of living with a chronic illness. For example, “satya” is a principle about truthfulness and not fooling yourself or others. Ms. Martin’s explanation of satya includes very practical, accessible examples such as “If someone asks you how you’re doing, you don’t always have to say you’re fine. Be honest with yourself and those around you.” The term “brahmacharya” is usually used to describe sexual abstinence or celibacy, but that’s actually an oversimplification as bramacharya is a bigger concept about protecting your energy. Ms. Martin points out this can also mean “ridding your life of the things that drain you.” She goes on to give specific examples of ways she has abstained from work, people, and relationships that drain her. It’s rare to find a beginner yoga book that isn’t focused ONLY on yoga poses, so this is a huge plus in my mind. In fact I think it would have been cool to see a whole chapter focused on each yama and niyama and how it relates to living with a chronic illness—I bet many people could relate to at least some of the explanations, even without a chronic illness..

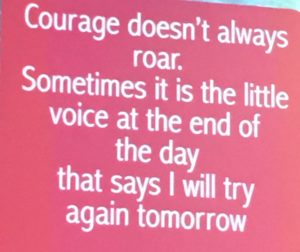

The practices are doled out in bite-sized pieces. Lots of books on yoga practice start out with “practice for 30 minutes” or “do this whole set of yoga poses.” This one is pretty refreshing in that the message is a consistent “do what you can, when you can—and that might be different today and tomorrow.” The first practice doesn’t even come in until Chapter 3, and that first practice is “savasana,” often referred to as “corpse pose” or out here in America as “final resting pose.” These small bites can be explored one at a time, and eventually you might choose to string them together into a practice. A visual guide at the end of the book helps with this.

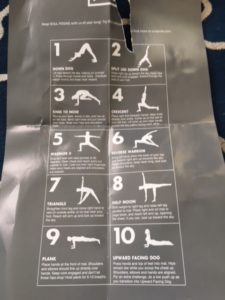

The physical yoga poses are fairly simple: savasana, seated forward fold, sukhasana (seated cross-legged), cat/cow, balasana (child’s pose), adho mukha svanasana (downward-facing dog), side plank, tadasana (mountain pose), vrksasana (tree pose), utkatasana (chair or awkward pose), “be free” (chest opener/movement). Each pose is introduced with a relatively simple line drawing. Overall I like the line drawings, and find them more useful than the typical yoga stick-figures, but I dislike the one for vrksasana as it shows the heel of the raised foot pressed into the knee of the standing leg (a big yikes, especially if you have delicate joints). I’m also not a huge fan of the one for downward-facing dog, as it looks a lot like me in my early yoga practice—overly rounded lumbar curve/collapsed spine. Otherwise, I would have liked to see more of these line drawings, especially to illustrate the alternative suggestions for ways to adapt the pose to your body.

Every yoga pose has numerous alternatives. Early in the book, Ms. Martin advocates for using props (chapter 4, “prop yourself up”) to make the yoga pose suit your body, instead of trying to mash your body into the pose. This is advice all people practicing yoga should heed. (I’m reminded of a story where one of my yoga teachers was teaching a class and offered a block to a student in her Level 2 class. The student refused, saying: “But I’m a Level 2 student!” My teacher replied, “And this is a Level 2 block.”) Everyone’s anatomy is just slightly different, and your shorter torso many not allow you to do things my longer toros permits me to do; whether your hands touch the floor is a function of bone length, not just flexibility. Lest you think Ms. Martin is advising everyone buy a bunch of yoga props, she specifically suggests using many items most of us already have available to us, including a wall or sofa. Ample suggestions for modifications and substitutes makes the practice accessible to just about anyone.

The end of the book has resources that are useful to people who just want a refresher or reminder of what to do. The “Quick Guide: Daily Practice” lists five elements (Breathe, Move, Close Your Eyes, Meditate, Set an Intention) with a sentence or two regarding each. These five elements are things literally anyone can do, even if they do not have a lot of time, space, or energy to devote to a practice. The “Move” component doesn’t suggest you need a specific series of yoga poses, but rather says “Wiggle your toes, go for a walk, practice a few poses. Every day do what feels good for you.” This type of movement is accessible no matter what your body is doing or feeling. Next, there is a “Reference Library” which repeats the yoga poses discussed in each chapter and the philosophical point Ms. Martin associated with each, plus the line drawing that originally accompanied the pose in the text.

Conclusion: Give It A Read?

Overall, I think this is a worthy read for those who have been diagnosed with a chronic illness, even if they have no interest in yoga poses—you can ignore that content and still get value from reading the book. I appreciate Ms. Martin’s personal insight. If you, or a loved one, live with a chronic illness—especially one that is “invisible” or one that includes living with chronic pain—I do recommend you check out The Yoga Prescription when it is released in January 2022.